What is Bodywork?

At best, bodywork is a systems-level therapy addressing physical, mental, and emotional interdependencies at the same time.

At worst…well, I could write for hours about my experiences of poor bodywork but that is best left for another time.

A generic term—bodywork—covers hundreds of modalities which focus on the body as a route for therapeutic change.

Clients receive bodywork for many reasons: emotional and mental regulation as well as acute and chronic physical symptoms.

The practitioner can use their hands to manipulate tissues and joints (e.g. massage) or they can provide instruction for you to move your own body in a certain way (e.g. yoga). We can also do bodywork ourselves but, here, I will stick to what constitutes professional therapeutic bodywork.

Leisure vs Therapy

When it comes to manual modalities, it is crucial to distinguish between leisure or therapy. Mistakes can be embarrassing for all concerned.

I propose that bodywork is not part of the beauty industry. Although a spa massage is wonderfully relaxing (and relaxation has many therapeutic benefits), there is usually no assessment or treatment plan and practitioners often follow set routines.

Nor is bodywork part of the sex industry. Therapeutic bodywork does not include massage used as a precursor (or cover) for sex work although there is a great deal of confusion among the public about this distinction—a confusion compounded by the UK government’s pandemic advice classifying all close contact bodywork as ‘massage parlours’ . It is almost as if politicians’ only experience of human contact has been through the sex industry.

Therapeutic bodywork involves both assessment and personalised treatment plan making each session unique.

The amount of physical contact involved varies from hands-on intervention to hands-off instruction. You will be familiar with the both manipulation of massage and the instructional guidance of a yoga teacher. Many modalities such as Feldenkrais, chiropractic and osteopathy, successfully combine manual intervention with instruction.

The degree of client engagement varies from passive to engaged. We tend to be more passive when receiving manual bodywork than when performing mindful movement.

Of course, manual techniques vary between modalities but, as a receiver, you are most likely to notice the quality of touch; is it light or deep; responsive or directive; busy or still?

This quality of touch brings us to what I consider to be the most important defining feature of bodywork—the practitioner themselves.

A technique is only as good as the person implementing it

photo: Swedish massage

The Role of the Practitioner

One practitioner might know some amazing bodywork techniques but have such a dominant personality that your sessions feel invasive; another practitioner might have an effective skillset but it feels to you like they are not really getting to the heart of the matter. Clients choose their bodywork practitioner based on the person more than the modality of bodywork.

It is because the mindset of the practitioner is so influential that individual practitioners often name their particular approach after themselves. Alexander Technique named after Frederick Mattieus Alexander; the structural integration approach known as Rolfing is named after Ida Rolf, and the particular type of chiropractic called McTimoney chiropractic is named after John McTimoney. People even trade mark their names to their bodywork approach.

We could say that there are as many types of bodywork as there are practitioners; but that isn’t very helpful. This observation, though, does highlight that the way bodywork works has more to do with the character of the practitioner than any particular modality they are offering.

There are two characteristics of practitioners which greatly influence how bodywork works:

1. the practitioner’s conceptual model of the body (how they think your body works), and

2. their habitual way of thinking (the way they process information about your body).

1. What they think

You might (understandably) assume that everyone shares the same conceptual model of how bodies work; there must only be one way, surely? But this is not so—even within the mainstream.

The biggest division is between those using what is called the biomedical model[1] and those working with an alternative.

Complementary bodyworkers use the biomedical model which your physician understands.

The reductionist nature of biomedicine not only splits mind from body, it also splits the body into functionally and structurally isolated parts.

Seeking help for foot pain, you will come across complementary bodyworkers who will address only the region of your foot as if it existed in isolation. If you are fortunate, you will find a complementary bodyworker such as a structural integrationist who acknowledges and treats the physical connectivity. Your foot pain may, for example, be coming from a distortion in soft tissue alignment from an old neck injury. There are far too many practitioners clinging to the out-moded idea that a foot problem is always only a foot problem.

There is also tacit pressure on complementary bodyworkers to only address physical symptoms. This split of mind from body remains so prevalent that any attempt to link physical, emotional and psychological conditions (that anxiety can tighten neck muscles leading to hand numbness, for example) elicits raised eyebrows even though such practitioners are adhering to an evidence-based psycho-biomedical. There is irrefutable evidence of mind-body interaction not yet filtering through to public consensus.

Strictly speaking such practitioners are holistic practitioners as they are addressing the whole person (physical emotional and mental) but this term has been misused to the point of being useless.

The public are often fearful of bodyworkers addressing anything other than their physical symptoms. Suggesting to a client that their neck pain might have emotional origin can be offensive. As a result, even complementary bodyworkers often go along with the idea that neck pain is always just a neck problem.

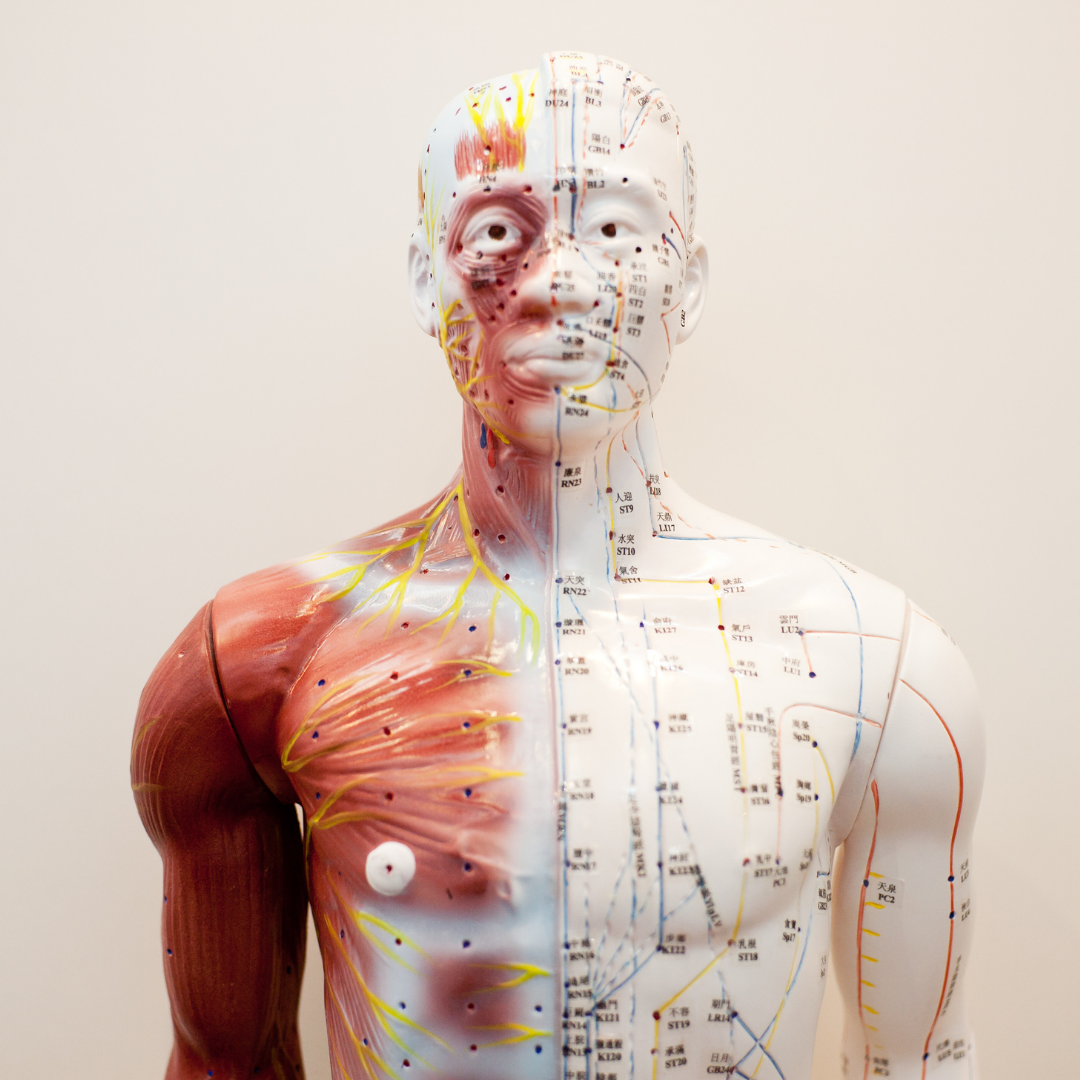

Alternative bodyworkers, on the other hand, are working from models of health which differ (often radically) from the biomedical model.

These models of how bodies work include meridian theory of acupuncture, shiatsu, Thai massage, Anma and Ayurveda; models of rhythms, pressures and pulsing used in craniosacral therapy, Bowen, and zero balancing. Some alternative models of how bodies work are valid but different perspectives based on experiential evidence. Others are a cross-cultural muddled mess of nonsense. Again, this has much to do with the mindset of practitioner; whether they have they sought out and studied a traditional craft (often, for decades) or taken a short course at the local FE college. Your discernment is essential.

The main attraction of bodywork based on alternative models of human health is that it overtly assumes the integration of physical, emotional, and mental health.

The main attraction of bodywork based on alternative models of health is an assumption of integration of between physical, emotional and mental health.

[photo: meridian theory]

2. How they think

The way a practitioner processes information—the way they think—is a major influence of the type of bodywork you will receive.

According to psychologists, we humans have two main ways of thinking, loosely divided into rational-analytical and experiential-intuitive.

Although we use both ways of thinking, we habitually trust one more than the other so a rational-analytical thinker will assess, diagnose and decide on a mode of treatment for a client’s physical problem. They will take measurements and write them down, refer to data for comparison. They will have a predictable response to a presenting symptom so that their treatment is replicable, repeatable and accountable.

An experiential-intuitive thinker will establish a sensory dialogue of action-reaction allowing intuitive insights to guide the treatment. They might, for example, offer a rotation to your shoulder and be guided by your unconscious physical response or your breathing pattern to decide where and what to do next. Each session is therefore unique and unrepeatable.

At the extremes, these two types of thinkers do not understand each other and can both be dismissive of the other’s approach. In practice, effective practitioners use a range of skills and techniques, selecting ways of working and ways of thinking that are optimal, dipping in and out of rational-analytical mode and experiential-intuitive mode as necessary; integrating passive and engaged states, utilising their hands or providing instruction; honing their craft through experience. As a client, you not only need to find the most appropriate modality but you also need to find a compatible practitioner. This relationship can be life-long. They are your integrated health care specialist.

[1] The biomedical model of health focuses on purely biological factors and excludes psychological, environmental, and social influences. It is considered the leading modern way for health care professionals to diagnose and treat a condition in most Western countries.